Introduction — a gentle start

Are you wondering are microbleeds in the brain dangerous? That is a smart and common question. Microbleeds are tiny spots of old blood in the brain. They do not always cause sudden symptoms. Doctors often find them by accident on MRI scans. Still, their meaning can change with your age, health, and medicines. This article explains microbleeds in plain words. We will cover what they are, how doctors find them, what causes them, and when they matter. You will also get clear answers about risk, treatment, and steps you can take. I wrote this to be easy to read and useful. If anything sounds worrying, please talk to your doctor about your own MRI and health history.

What exactly are microbleeds?

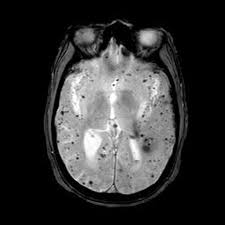

Microbleeds are very small spots left by tiny leaks of blood in the brain. They are not active bleeds. Instead, they are leftovers. The blood breaks down and leaves iron-rich pigments called hemosiderin behind. On special MRI scans, these spots look dark. Radiologists call them cerebral microbleeds or CMBs. They are usually under 5 mm in size. The fact they are small can be misleading. Small does not always mean harmless. How many there are and where they sit matters. The term is an imaging label. It tells doctors that a tiny vessel in the brain once leaked blood.

How doctors find microbleeds on scans

Doctors use MRI to see microbleeds. A sequence called susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) or T2* picks them up best. These scans are more sensitive than older MRI types. Higher magnetic field strength and better image settings reveal more spots. That means a scan with better technique may show microbleeds that another scan missed. This is important when comparing scans over time. Radiologists count and map the spots. They also note whether the microbleeds are deep or near the brain surface. The imaging details help doctors guess the likely cause and possible risk.

Common causes of microbleeds

Two main disease types cause most microbleeds. One is hypertensive small vessel disease. This is linked to long-standing high blood pressure. It tends to cause microbleeds deep in the brain. The other is cerebral amyloid angiopathy. That involves protein build-up in vessel walls. It causes microbleeds near the brain surface, in lobar regions. Other causes include trauma, blood disorders, and rare genetic conditions. Age is a big factor. The older a person is, the more likely microbleeds will show up on scans. Clues from the MRI help doctors pick the most likely cause.

Where in the brain do microbleeds appear?

Microbleeds can show up in different brain zones. Deep microbleeds appear in the basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, or cerebellum. These deep spots are often linked to high blood pressure. Lobar microbleeds sit in the outer brain cortex and nearby white matter. Lobar spots are commonly tied to amyloid angiopathy, especially in older adults. The pattern matters. A deep pattern suggests one cause. A lobar pattern suggests another. Doctors use the pattern to guide decisions about treatment and future risk. Maps of microbleed locations help with clinical judgment.

Who is more likely to have microbleeds? Risk factors

Some people are more likely to have microbleeds than others. Age is the strongest risk factor. People over 60 have more of them on average. High blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes raise risk too. A history of stroke or small vessel disease increases the chance. Genetic and rare disorders can cause microbleeds in younger people. Certain blood-thinning medicines and head injuries may also play a role. The total number of microbleeds grows with some of these risks. Knowing your risk helps doctors weigh monitoring and treatments.

Can microbleeds cause symptoms?

Microbleeds themselves are usually silent. Most people with microbleeds do not notice a clear new symptom from the tiny spots. Often, doctors find them when they look for other problems. However, a lot of microbleeds, or microbleeds in certain areas, link to worse outcomes over time. They are markers of fragile blood vessels. In some people, microbleeds appear along with small strokes, gait changes, or memory trouble. But a single small microbleed rarely causes major immediate symptoms. Clinical context is key to understanding what a finding means for one person.

The big question: are microbleeds in the brain dangerous?

Short answer: sometimes. The presence of microbleeds raises certain risks. People with microbleeds have a higher chance of future bleeding in the brain. They also face elevated risks of ischemic stroke and dementia. That said, the absolute risk for any one person varies. It depends on the number, location, and underlying cause. A single lobar microbleed in an older person is not the same as many deep microbleeds in someone with uncontrolled hypertension. Doctors weigh the scan results against the person’s age, health, and medications to decide how dangerous the spots are.

Microbleeds and stroke: how they link together

Microbleeds act as a warning sign for future brain events. Studies of many patients show that people with microbleeds have higher rates of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. The more microbleeds someone has, the higher the relative risk. Still, the absolute number of future hemorrhages may be small for many people. In some situations, the benefit of preventing an ischemic stroke may outweigh the increased bleeding risk. That is why stroke teams assess microbleeds when they plan medicines and procedures. Each case needs a personalized balance.

Microbleeds and thinking problems: dementia links

Research shows a link between microbleeds and cognitive decline. People with microbleeds are more likely to develop dementia over time. The link is stronger when microbleeds appear with other signs of small vessel disease. These include white matter changes and tiny past strokes on imaging. Microbleeds may reflect long-term vessel damage that affects brain networks. But microbleeds are one of many factors. Genetics, lifestyle, and other brain diseases also matter. Treating vascular risk factors may help slow decline in many cases.

What microbleeds mean for blood thinners and antiplatelets

One of the hardest questions for doctors is how to manage blood thinners when microbleeds are present. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs lower the risk of clot strokes. But they can raise the risk of bleeding, including brain bleeding. Studies show that microbleeds predict a higher intracerebral hemorrhage risk in people on blood thinners. Yet stopping blood thinners may raise the risk of ischemic stroke, especially in atrial fibrillation. Newer drugs often carry lower brain-bleed risk than older ones like warfarin. Decisions are complex and need specialist input based on each person’s overall stroke and bleed risk.

Treatment: what doctors can do right now

There is no pill that removes microbleeds once they are on an MRI. Treatment focuses on controlling what caused them. For most people, that means tight blood pressure control and treating heart and metabolic risks. Doctors also review medicines that affect bleeding. In some cases, teams will choose safer blood-thinning options or adjust doses. Rehabilitation and cognitive therapies help when microbleeds are part of broader brain damage. Regular follow-up and repeat imaging may guide care over time. The aim is to lower future risk and keep the brain healthy.

How to reduce your risk and protect your brain

You can act on many risk factors linked to microbleeds. Keep blood pressure in a healthy range. Quit smoking and limit alcohol. Manage diabetes, cholesterol, and weight. Stay active and eat a balanced diet. These steps lower small vessel damage and help brain health. Avoiding head injury also helps, especially in older age. If you take blood thinners, discuss the risks and benefits with your doctor. Good heart health often equals better brain health. Small daily steps add up over years.

When should you see a doctor about microbleeds?

See your doctor if an MRI report mentions microbleeds and you feel worried. Bring the scan images if possible. Discuss your full health history, medicines, and stroke risk factors. If you have new weakness, speech trouble, or sudden severe headache, go to the emergency room. For long-term planning, a neurologist or stroke specialist can explain the scan meaning. They can help decide on medicines, tests, and follow-up. Having a clear plan reduces anxiety and helps protect your brain health going forward.

Common myths about microbleeds, cleared up

Myth: one microbleed means immediate danger. Fact: most single microbleeds do not cause sudden crisis. Myth: microbleeds always mean dementia is coming. Fact: they increase risk, but dementia depends on many factors. Myth: microbleeds mean you must stop all blood thinners. Fact: stopping treatment can raise stroke risk, so decisions are nuanced. Doctors use the full picture to guide choices. Learning facts helps you make calm, informed decisions with your clinician.

Frequently Asked Questions (6)

Q1 — If an MRI report says “microbleeds,” should I panic?

No. Finding microbleeds is not an emergency in most cases. Many people have one or two tiny spots and live well. The key is context. Your age, blood pressure, medicines, and other brain findings matter. A specialist can explain the likely cause and next steps. Often the plan is monitoring and better control of vascular risks. If you also have sudden symptoms like weakness or severe headache, seek emergency care. Otherwise, a calm follow-up visit is the usual first step.

Q2 — Will microbleeds cause a stroke soon?

Microbleeds raise future stroke risk, but they do not guarantee a stroke. Studies show higher relative risk for both bleeding and clot strokes. The risk depends on the number and pattern of microbleeds and overall health. Good management of blood pressure and heart health lowers the chance of future strokes. Your doctor can estimate your personal risk and help choose medicines and lifestyle steps that match your situation.

Q3 — Should I stop aspirin or other antiplatelets if microbleeds are found?

Do not stop prescribed medicines without talking to your doctor. Stopping antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs can raise the risk of ischemic stroke in some people. The choice depends on why you were taking the drug and how many microbleeds you have. In some patients, changing to a different drug or adjusting dose is safer. A specialist will weigh risks and benefits to find the best plan for you.

Q4 — Can microbleeds be treated or reversed?

There is no treatment that erases past microbleeds on MRI. They are traces of past tiny leaks. The important steps are preventing new leaks and reducing vascular harm. This includes blood pressure control, lifestyle changes, managing diabetes, and careful use of blood-thinning medicines. Some therapies aim to reduce future risk rather than reverse old spots. Regular follow-up helps track changes and adjust care.

Q5 — Do younger people get microbleeds?

Yes, but less often. In younger people, microbleeds are rare and often linked to specific causes. These may include trauma, blood disorders, or genetic vessel problems. When microbleeds appear in younger adults, doctors usually investigate further for uncommon causes. In older adults, microbleeds are more commonly due to age-related vessel changes like hypertension or amyloid angiopathy.

Q6 — How often should scans be repeated if microbleeds are found?

There is no single rule. Doctors decide based on the cause, number of microbleeds, symptoms, and treatment plan. Some people have repeat imaging after months to check for change. Others need only clinical follow-up unless symptoms occur. If medications are being changed for safety, a follow-up scan may be reasonable. Your neurologist or stroke team will recommend the best timing for you.

Conclusion — clear next steps and encouragement

So, are microbleeds in the brain dangerous? The honest answer is: sometimes they are, and sometimes they are not. They are an important clue about the health of tiny brain vessels. That clue helps doctors weigh future risks and make choices about medicines and prevention. The most useful actions are simple and proven: control blood pressure, manage heart health, avoid smoking, and keep active. If your MRI shows microbleeds, talk to a neurologist or stroke specialist. Together, you can make a plan that fits your life and lowers risk.